This post is also available in: German Czech Polish

The analyse:berg issues are packed with sober figures and anonymous accident descriptions by the alpine police or experts. “Alpine technical reports”, in other words. Rarely do we have the opportunity to learn from the subjective experiences of others who have been involved in an avalanche accident. Even rarer is an accident in which a completely buried ski tourer has been successfully resuscitated. Stephan Birkmaier was the fully buried victim, his friend was partially buried and carried out the resuscitation. Both describe the events from their perspective.

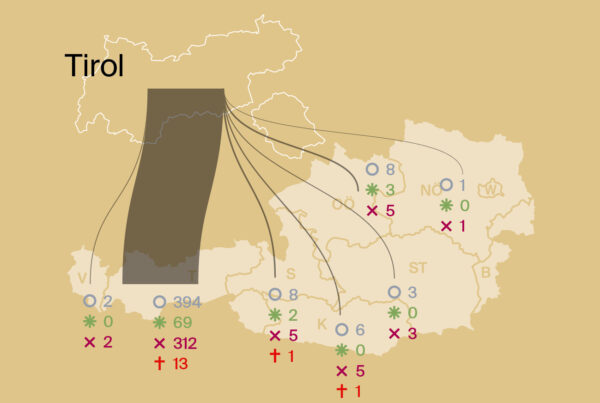

The accidental avalanche. For Sunday, April 3, 2022, the Norwegian Avalanche Warning Service (varsom.no) predicted danger level 3 in the Sør-Troms area with the headline: "The avalanche danger is highest in places that have wind slabs above persistent weak layers". This old snow problem was predicted in all exposures between 400 and 1,100 m, above 300 m from N to SE a new snow problem with danger level 2 was also issued.

The dry snow slab was triggered by the ski touring group on the ascent in a western flank and was approx. 500 wide and approx. 250 long. The snowpack examination revealed an ECTP12@62cm (weak snowpack stability) with a thin, angular weak layer above a melt crust. A total of three people were partially buried and one completely buried.

The photo was taken after the completely buried author was removed by an NH90 Coast Guard helicopter (RoNAF) by an AW101 SAR helicopter of the 330 Squadron (RoNAF), which was alerted later and also lowered an air rescuer to inquire about the condition of the remaining group members.

Photo: Torgeir Kjus, Royal Norwegian Air Force (RoNAF)/330 Squadron

#1

How quickly life can be over.

And a fresh start is the exception rather than the rule.

“Today I have no neurological limitations. I go about my work as an anesthetist and don’t notice any impairments. Only my sternum has not healed and regularly reminds me of my second birthday – for example when I sneeze with pain.” This is how this article by Stephan Birkmaier begins. The aching sternum is from the resuscitation by a friend after Stephan was dug out of an avalanche in Norway, buried two meters deep.

Stephan Birkmaier

Specialist in anesthesia and intensive care medicine

Anticipation

We weren’t professionals who stormed to the summits every free day, but in the local Alps we were able to set ourselves ever greater goals after a few avalanche, glacier and high-altitude medicine courses. In the Monte Rosa region, we climbed several peaks such as the Dufourspitze. Outside of the courses, we always went without a mountain guide and made our own decisions.

In April 2022, we, a group of five friends, wanted to go ski touring in Norway. As we didn’t know the area, we booked a guided tour through a mountain school.

The anticipation was great. To stay in shape, we took every opportunity for training tours. When packing my equipment, I decided to take my airbag rucksack with me. I go almost exclusively with an airbag, except on multi-day tours when there is not enough space in my rucksack.

However, a friend who flew two days before us was told at the airport that his carbon cartridge was not allowed through security. As I had the same backpack, I didn’t want to risk having to send it back too. I thought about quickly borrowing or buying another model, but time was very short and the thought “We are a guided group and will certainly take it easy” made me leave the airbag at home – a fatal mistake.

Norway

Our arrival went smoothly and the lodges were superbly located right by the sea with breathtaking views of the water and steep mountains. Our group was joined by a second group from the same mountain school. Each had their own mountain guide, but we undertook the tours together.

The evening before the tours, all the participants and mountain guides sat together to discuss the situation. The first tour was unspectacular due to bad weather and poor visibility. However, the weather forecast promised bright sunshine for the next day, but with strong winds – our opportunity to explore the area. In the preliminary discussion, we took into account snow drifts and chose a flat ascent route away from steep slopes.

Accident day

The following morning, we found ourselves in one of the most beautiful areas of Norway, the Ånderdalen National Park. The previous day had already shown a difference in experience and fitness between our two groups. On this day too, we were significantly faster and soon left the second group far behind us.

To make the wait in the cold wind more pleasant, our mountain guide suggested we take a short detour to a surrounding slope and return to the original route later. He checked the slope gradient on his cell phone and two of my colleagues joined him. The decision to tackle the climb was therefore a joint one.

Shortly afterwards, we were standing at the foot of the slope, which now looked much more impressive than a few minutes earlier. To be honest, if we were traveling alone among friends, we wouldn’t go up it. I expressed my unease to one of my friends, we discussed and deliberated, but the mountain guide seemed competent and confident. So we carried on and didn’t share our uneasy feeling with the others.

After a few hairpin bends, the mountain guide told us to keep a safe distance of 15 meters. I couldn’t shake my uneasy feeling. I spoke to another colleague about it, but he also trusted that the mountain guide could assess the situation better than we could. I briefly considered turning back alone, but my pride prevented me from doing so. Two minutes later, I experienced the consequences of this decision.

The ski tour. The plan was to climb Kvænan (964 m), a popular ski tour summit on Senja, the second largest Norwegian island about 350 km north of the Arctic Circle, which belongs to the province of Troms. The summit of this destination can be seen in the upper right corner of the photo in the background. The first, faster group decided to turn "left" into a basin as an unplanned intermediate destination, ascend, descend and then continue together with the second group up Kvænan. During the ascent, they triggered the snow slab. - The photo was taken during the approach of the SAR helicopter of 333 Squadron, which was alerted after the completely buried ski tourer had already been flown out by another helicopter.

Photo: Torgeir Kjus, Royal Norwegian Air Force (RoNAF)/330 Squadron

Avalanche burial