This post is also available in: German Czech Polish

This article was published in the summer 2024 issue of the ÖKAS trade magazine analyse:berg. Become a subscriber to analyse:berg. You will receive the magazine conveniently delivered to your home as soon as it is published and support the work of ÖKAS at the same time.

What happened in the high mountains in 2024?

Author:

Lukas Furtenbach

Founder Furtenbach Adventures

China, ceasefire & all 14 or 7

When China reopened the Tibetan north side of Everest to foreigners in spring, for the first time since 2019, and later allowed access to Cho Oyu and Shishapangma in autumn, records quickly began to fall. With these long-inaccessible peaks finally back in play, a wave of climbers joined Reinhold Messner in the exclusive club of those who’ve summited all 14 eight-thousanders – style of ascent not withstanding. When it comes to summit collections, it seems, the summit is what counts, not how you get there.

Later in October, a ceasefire with rebels near the Carstensz Pyramid allowed ascents for the first time since 2019. Under the protection of heavily armed soldiers, many took advantage of this rare opportunity to complete their Seven Summits collection – in the Messner version.

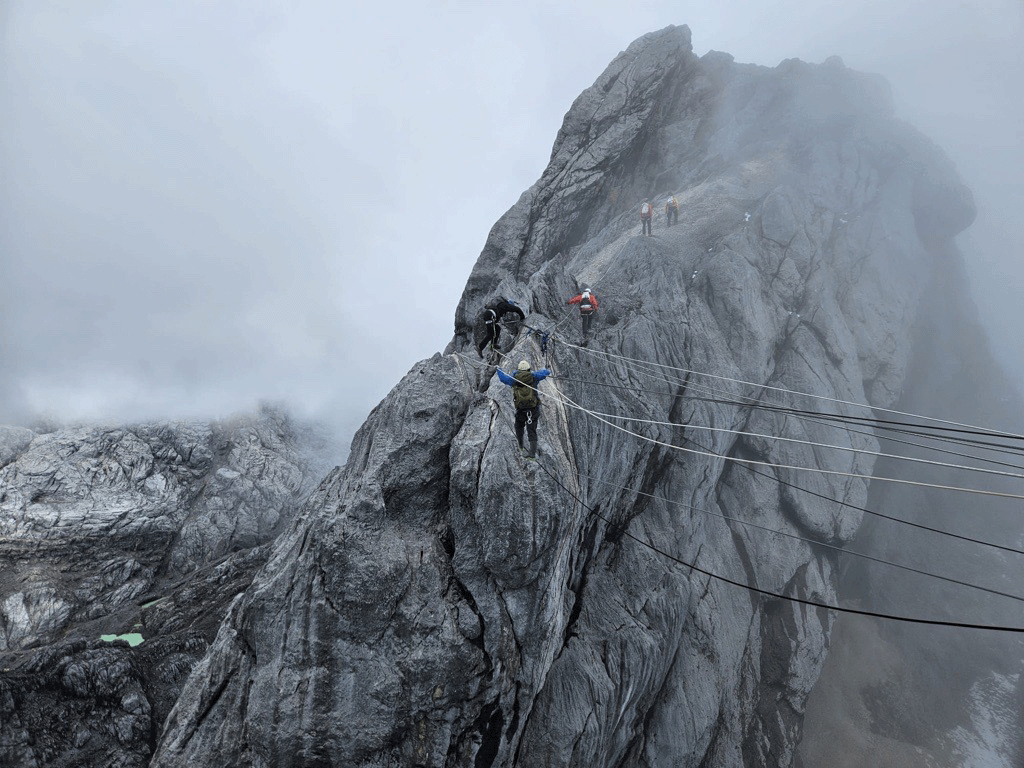

In recent years, high-altitude mountaineering has evolved rapidly. Technology, advanced equipment, and above all, the commercialization of nearly every aspect of the sport have reshaped the image of the traditional “adventurer”. While technical innovation and infrastructure have undeniably improved safety and comfort, the increasing commercialization has raised questions about the loss of authenticity and tradition. But what do those words really mean in a modern mountaineering context? More on that shortly.

Coming soon: Everest in a Week

Over the past few decades, technology has revolutionized high-altitude mountaineering. Satellite communications and modern weather forecasting allow for constant connectivity, safer planning and real-time adaptation. Gear innovations, from ultra-light tents and high-efficiency oxygen systems to heated clothing, have made mountaineering safer and more accessible.

Pre-acclimatization at home in altitude-simulating environments, or more recently through specialized noble gas treatments, is redefining high-altitude mountaineering, both in terms of the duration of expeditions as well as strategy and tactics. Climbing an 8,000-meter peak in under two weeks, a 6,000er in one week, or combining multiple summits in a short expedition is no longer remarkable. We are just a step away from „Everest in a week,” slated to launch in spring 2025.

Fast & Safe

Last year also saw an increase in reports of new FKTs (Fastest Known Times) on major peaks. Among the most impressive was Tyler Andrews’ 9-hour, 52-minute ascent of Manaslu (8,163 m) from base camp to summit, without supplemental oxygen, in September. Just a month later, he clocked a 3-hour, 52-minute ascent of Ama Dablam (6,812 m), another stunning achievement.

Women, too, are breaking speed records. Fernanda Maciel set a new FKT on Carstensz Pyramid with a round-trip time of 1 hour and 48 minutes, while Laura Dahlmeier posted a female FKT on Ama Dablam in 8 hours and 24 minutes. Both records were set in the autumn, adding to a growing list of speed accomplishments by both men and women on various peaks and routes.

All of these FKTs took place within the framework of commercial expedition infrastructure and followed normal routes. This infrastructure, especially fixed ropes in hazardous or technical sections – provided the crucial safety net that made such rapid ascents possible.

Fallen Gladiators

Yet despite all this progress, the frequency of accidents, fatalities, and near-misses in the high mountains remains unchanged. The Russian „kamikaze expedition“ on Dhaulagiri left five dead; Mike Gardner perished on Jannu, and Ondro Husarka on Langtang Lirung. The latter two were climbing in what’s often described as a „clean“ or „pure“ style – eschewing safety margins and embracing high personal risk. This style, regarded by many within the alpine community as the only ”true” form of ascent, celebrates authenticity and tradition in their most extreme form, heightening exposure and the possibility of death. Welcome to the Circus Maximus.

When these mostly young (and male) gladiators fall victim to this ethos, and they do, in large numbers and with alarming regularity, there is consternation in the community and media, mourning their loss while celebrating their commitment and purity of style. Even in death, their choices are glorified, inspiring others to follow the same perilous path.

This polarization – between a commercialized version of mountaineering on the one hand, and the pursuit of “authenticity” through potentially fatal ideals on the other – produces some strange contradictions. Take, for instance, YouTuber Inoxtag, whose Everest ascent video reached millions within hours. Or influencers tackling all 14 eight-thousanders as a sudden career change. Or self-proclaimed purists climbing “new routes” just meters away from the bundles of fixed lines on Ama Dablam. These headlines are regularly punctuated by the deaths of so-called pure alpinists – deaths that, unlike those of “mountain tourists,” are still viewed as noble and untouchable.

„The ’summit philosophy‘ shifted in 2024.

Expeditions once seen as extreme and demanding

have increasingly become formulaic tourist experiences

or mere platforms for record-setting.

Both mountaineering and adventure tourism

have lost the sense of innocence they once held.“

Links & Publications:

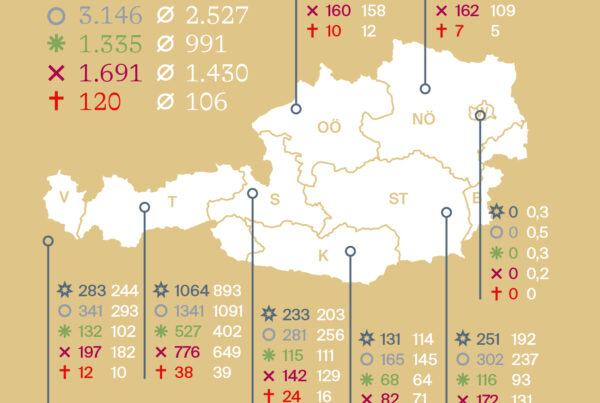

- Trade magazine analyse:berg Winter 2024/25 (observation period: 01.11.2023 to 31.10.2024) Orders in the store.

- Trade magazine analyse:berg summer 2024 (observation period: 01.11.2022 to 31.10.2023) – Orders in the store.

- Subscription magazine analyse:berg Winter & Summer

- Alpine Primer Series of the Board of Trustees

- Alpine Fair / Alpine Forum 2024

- Editor-in-chief: Peter Plattner peter.plattner@alpinesicherheit.at

- Contact ÖKAS:

Susanna Mitterer, Austrian Board of Trustees for Alpine Safety, Olympiastr. 39, 6020 Innsbruck, susanna.mitterer@alpinesicherheit.atTel. +43 512 365451-13